Alcoholic hepatitis is a severe form of liver disease that arises from excessive alcohol consumption, representing a significant public health concern that impacts millions of individuals worldwide. The Regeneration Center would like to shed some light on the complexities of alcoholic hepatitis, exploring its causes, symptoms, diagnosis, and current treatment approaches. Furthermore, we will look into the promising role of umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal stem cell therapy as a potential treatment avenue for this challenging condition, examining the latest research and potential benefits this innovative non-surgical approach holds.

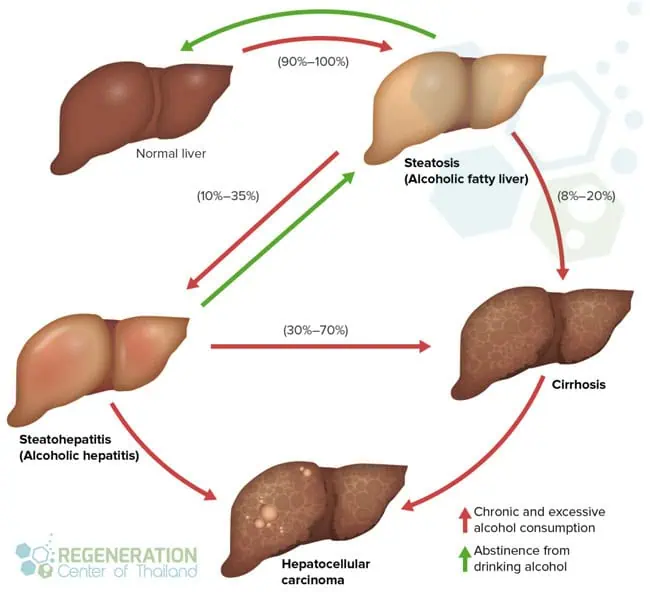

Alcoholic hepatitis (AH) is a specific type of alcohol-related liver disease characterized by inflammation of the liver and decompensated liver cirrhosis. This inflammation isn’t simply a mild reaction; it signifies significant damage to liver cells (hepatocytes), impairing the liver’s ability to perform its vital functions, such as filtering toxins from the blood, producing bile for digestion, and storing essential nutrients. Unlike some other forms of alcoholic liver disease that develop gradually over decades, AH can develop rapidly, sometimes within weeks of heavy drinking.[1]

The severity of AH can vary greatly, with some individuals experiencing mild, short-lived symptoms. In contrast, others develop severe liver fibrosis and acute-on-chronic liver failure that can be life-threatening. The unpredictable nature underscores the seriousness of the condition and the importance of early diagnosis and therapeutic intervention.

While excessive and prolonged alcohol consumption is the primary cause of alcoholic hepatitis, it’s not as simple as saying everyone who drinks heavily will develop the disease. Individual susceptibility plays a significant role, with genetics playing an essential part. This is also true when considering treatments like human mesenchymal stem cells for liver repair. Certain gene variations, particularly those involved in alcohol metabolism, can make individuals more vulnerable to the toxic effects of alcohol on the liver. For example, variations in genes encoding alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) and aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) enzymes, responsible for breaking down alcohol in the body, can influence the risk of developing AH.

Beyond genetics, other factors contribute to the development of AH. Gender is a factor, with women appearing to be more susceptible to alcohol-induced liver damage at lower levels of consumption compared to men. This difference may be attributed to variations in alcohol metabolism, body composition, and hormonal factors between genders. Ethnicity also seems to play a role, with certain ethnic groups potentially experiencing a higher risk of AH. For instance, individuals of Hispanic/Latino descent may be more susceptible to AH, even with lower levels of alcohol consumption, compared to other ethnicities.[2]

Furthermore, the overall health of the liver before heavy drinking begins is crucial. Individuals with pre-existing liver conditions, such as fatty liver disease (hepatic steatosis) or hepatitis C, are significantly more vulnerable to developing AH. Fatty liver disease, often associated with obesity, metabolic disorders, autoimmune disease, pancreatitis, and diabetes, can progress to inflammation and fibrosis, making the liver more susceptible to alcohol-induced damage. Hepatitis C, a viral infection affecting the liver, can also lead to chronic inflammation and scarring, further increasing the risk of AH. Nutritional deficiencies can exacerbate alcohol’s effects on the liver, as can the co-abuse of other substances, such as certain medications or illicit drugs. These substances can put additional stress on the liver, compounding the damage caused by alcohol and potentially complicating a patient’s ability to benefit from stem cell therapy for liver failure.

After extended alcohol use, healthy liver tissue can be slowly replaced by atrophied or thinning scar tissue. When this scar tissue builds up, it can impede normal liver function and is categorized as liver cirrhosis. Severe liver cirrhosis is irreversible, but the combination of abstinence and liver stem cell therapy may be able to contain the disease and slow its progression. If liver cirrhosis goes untreated, it will lead to end-stage liver failure.

Alcoholic hepatitis presents a wide range of symptoms, often making it difficult to diagnose in its early stages. Some individuals may be completely asymptomatic, unaware of the damage being inflicted upon their liver. This silent progression makes regular medical checkups, and liver function tests essential for individuals with a history of heavy alcohol use. When symptoms do appear, they can range from mild and general to severe and life-threatening, necessitating comprehensive treatments that might include cell therapy for liver disease.

One of the most noticeable symptoms is jaundice, a yellowing of the skin and the whites of the eyes, which may also indicate the need for advanced treatments like cell therapy for liver disease. Jaundice occurs due to a buildup of bilirubin, a yellow pigment produced during the breakdown of red blood cells in the blood. Typically, the liver processes bilirubin, making it water-soluble and excreted in bile. However, a damaged liver with cirrhosis can’t perform this function effectively, leading to its accumulation in the blood and deposition in tissues, causing yellow discoloration. Fatigue is a common symptom, often described as a persistent lack of energy not relieved by rest.[3]

This profound tiredness can significantly impact daily life, exhausting even simple tasks. It arises from the liver’s impaired ability to convert stored energy into usable energy, leading to a constant low-energy state. Loss of appetite is another warning sign, often accompanied by unexplained weight loss. This reduced desire to eat can be attributed to a combination of factors, including liver dysfunction, hormonal imbalances, and a buildup of toxins in the blood that can suppress appetite.

Digestive symptoms are frequent, with nausea and vomiting being common complaints. These symptoms stem from the liver’s diminished capacity to process toxins and produce bile, leading to digestive issues such as IBD and Crohn’s disease. As AH progresses, individuals may experience abdominal pain, particularly in the upper right quadrant, where the liver is located. This pain can range from a dull ache to sharp, stabbing sensations. The pain often worsens with movement or deep breathing and can be exacerbated by the accumulation of fluid in the abdomen (ascites). Fluid retention, frequently manifesting as swelling in the legs, ankles, and abdomen (ascites), can also occur due to the liver’s inability to regulate fluid balance. The damaged liver can no longer effectively produce albumin, a protein essential for maintaining average fluid balance in the body, leading to fluid leakage into tissues.

Diagnosing alcoholic hepatitis is a multifaceted process that requires a comprehensive evaluation by a healthcare professional. No single test definitively diagnoses AH, so physicians rely on a combination of clinical findings, lab results, and imaging studies to make an accurate diagnosis. The diagnostic journey typically begins with a thorough medical history review. A physician will inquire about the individual’s alcohol consumption habits, asking about the quantity and frequency of alcohol intake. They’ll also assess drinking patterns over time, as even periods of abstinence interspersed with heavy drinking episodes can contribute to AH.

A hepatologist will examine the individual’s overall health history, including any pre-existing conditions, family history of liver disease, medications, and other lifestyle factors. This detailed history helps paint a comprehensive picture of the individual’s risk factors for AH and provides valuable clues for diagnosis.

A physical examination is the next step. The physician will look for physical signs of alcoholic liver disease, such as jaundice, fluid retention in the legs or abdomen, brain fog, and tenderness in the upper right abdomen where the liver is located. Additionally, the potential for stem cell therapy for liver disease might be discussed depending on the condition’s severity. They may also assess for other signs of chronic liver disease, such as enlarged blood vessels on the skin (spider angiomas), redness of the palms (palmar erythema), or changes in the shape of the fingernails (clubbing). These physical findings, while not specific to AH, can indicate advanced liver disease.

Blood tests are crucial for evaluating liver function. Liver function tests (LFTs) measure the levels of certain enzymes and proteins in the blood that can indicate liver damage or inflammation. Elevated levels of liver enzymes, such as AST (aspartate aminotransferase) and ALT (alanine aminotransferase), can indicate liver injury. These enzymes are typically found inside liver cells, and their presence in elevated amounts in the blood suggests cell damage and leakage. Doctors will also check bilirubin levels, with elevated levels suggesting impaired bilirubin processing by the liver, a common finding in AH. This may prompt consideration of new treatments like mesenchymal stromal cell therapy. Other blood tests may include a complete blood count (CBC) to check for anemia and platelet count abnormalities, which can occur with liver dysfunction, and coagulation tests (INR, PT) to assess the liver’s ability to produce clotting factors.

Imaging studies visually represent the liver, allowing physicians to assess its size, shape, and structural abnormalities. Ultrasound is often the initial imaging test, providing a quick and non-invasive way to visualize the liver. It can detect signs of fatty liver disease, inflammation, and cirrhosis (scarring). If abnormalities are detected on ultrasound, further imaging with CT scans or MRI may be recommended to provide more detailed images and assess the extent of liver damage. In some cases, a liver biopsy may be necessary to confirm the diagnosis and evaluate the severity of alcoholic hepatitis. A liver biopsy involves obtaining a small sample of liver tissue, usually through a needle inserted through the skin and into the liver under ultrasound guidance. A pathologist examines The tissue sample under a microscope to look for characteristic signs of AH, such as inflammation, cell death (necrosis), and fibrosis (scarring). The biopsy can also help determine the stage of liver damage, which is useful when making treatment decisions.

The first and most vital step in treating alcoholic hepatitis is complete and permanent abstinence from alcohol. This means no amount of alcohol is considered safe. Continued alcohol consumption, even in small amounts, will worsen liver damage and significantly decrease the effectiveness of all treatments, including interventions like mesenchymal stem cells for alcoholic liver disease. Patients with AH need to eliminate alcohol from their lives to prevent further acute liver injury and improve their chances of recovery.

Alongside abstinence, nutritional support is paramount. A healthy, balanced diet rich in calories and protein supports liver regeneration. Malnutrition is common in individuals with AH, often due to poor dietary intake, malabsorption of nutrients, and increased metabolic demands. Dietary interventions usually involve working with a registered dietitian to develop a tailored meal plan that meets the individual’s nutritional needs. This plan typically includes increasing calorie and protein intake, ensuring adequate vitamin and mineral intake, and limiting sodium and fluid intake if fluid retention is present.

Medications play a role in managing alcoholic hepatitis and its complications. Corticosteroids, such as prednisolone, are often prescribed to reduce liver inflammation. These medications work by suppressing the immune system’s inflammatory response, which helps to reduce liver injury. However, corticosteroids also come with potential side effects, including weight gain, increased risk of infections, and developing osteoporosis, so their use must be carefully monitored. The decision to use corticosteroids is typically based on the severity of AH, with more severe cases often benefiting from their use.

Other medications may be prescribed to manage specific complications of AH. Diuretics can help reduce fluid retention (ascites) by increasing urine output and removing excess fluid from the body. Antibiotics can treat bacterial infections, which are more common in individuals with compromised liver function. The liver plays a crucial role in fighting infections, so a damaged liver can make individuals more susceptible to bacterial infections. In cases of severe alcoholic hepatitis that don’t respond to medical management, a liver transplant may be the only life-saving option. Liver transplantation involves surgically replacing the damaged liver with a healthy liver from a deceased donor. However, liver transplantation is a significant procedure with its risks and benefits, and not all individuals with AH are eligible for transplantation. Factors considered for transplantation include the severity of liver disease, overall health status, and the individual’s commitment to abstaining from alcohol after transplantation.

Stem cell therapy represents a revolutionary approach to treating various diseases, and its potential in addressing liver conditions like alcoholic hepatitis is fascinating. Stem cells for alcoholic cirrhosis offer a unique ability to differentiate into multiple cell types within the body, including liver cells. This characteristic makes them an up-and-coming tool for regenerating damaged tissues, offering hope for restoring liver function in individuals with AH. Unlike traditional treatment approaches that focus on managing symptoms and preventing further damage, stem cell therapy holds the potential to repair and regenerate damaged liver tissue directly.

The mechanisms by which stem cells can potentially treat alcoholic hepatitis are multifaceted and still under investigation. However, early research suggests several promising avenues:

The Regeneration Center offers several types of stem cells for treating alcoholic hepatitis, each with unique characteristics and potential advantages. For example, mesenchymal stem cells for alcoholic liver disease show promising regenerative capabilities.

The success of stem cell therapy hinges on the type of stem cells used and the quantities and methods by which they are delivered to the liver. We have explored various delivery methods, each with its advantages and disadvantages. Isolated and expanded stem cells can be delivered to the liver through intravenous (IV) intrahepatic, intrasplenic, intraperitoneal, or portal vein injections (PVI)

While stem cell therapy for alcoholic hepatitis holds immense promise, it is crucial to approach this emerging field with a balanced perspective, carefully weighing the potential benefits against the possible risks:

Ongoing research and clinical trials are the lifeblood of progress in stem cell therapy. We are actively working to answer critical questions and translate these promising findings into effective clinical treatments for alcoholic hepatitis. Future research will likely focus on:

Alcoholic hepatitis is a severe liver condition, but recent advances in medical research and UC-MSC+ stem cell therapy offer patients a viable alternative to traditional treatments and liver transplants. Stem cell therapy holds significant promise for regenerating damaged liver tissue and improving long-term outcomes for individuals with this challenging disease. As research progresses and our understanding deepens, stem cell therapy may emerge as a transformative treatment option, offering new hope for individuals battling alcoholic hepatitis and potentially revolutionizing the way we approach liver disease treatment. The potential to not only manage symptoms but to reverse liver damage and restore function makes stem cell therapy an incredibly promising avenue for the future of AH treatment.

Due to the varying degrees of existing liver damage and the current stage, all potential patients must provide recent medical documents and recent liver radiology scans for review. Isolated and enhanced liver stem cell therapy can be administered in multiple ways to reduce severe systemic and liver inflammation, thereby restoring liver health.

The Regeneration Center treatment for Alcoholic Hepatitis & Alcoholic liver disease with stem cells is an outpatient procedure that will require 10-12 days in Bangkok. After the treatment evaluation, a detailed medical plan will be provided. It will include specifics regarding the medical treatment, the exact length of stay needed, and the total costs for our treatment. To learn more, please contact us today.

[1] ^Wakabayashi M, McKetin R, Banwell C, Yiengprugsawan V, Kelly M, Seubsman SA, Iso H, Sleigh A; Thai Cohort Study Team. Alcohol consumption patterns in Thailand and their relationship with non-communicable disease. BMC Public Health. 2015 Dec 24;15:1297. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-2662-9. PMID: 26704520; PMCID: PMC4690366.

[2] ^ Chuncharunee L, Yamashiki N, Thakkinstian A, Sobhonslidsuk A. Alcohol relapse and its predictors after liver transplantation for alcoholic liver disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Gastroenterol. 2019 Aug 22;19(1):150. doi: 10.1186/s12876-019-1050-9. PMID: 31438857; PMCID: PMC6704694.

[3] ^ Gao B, Bataller R. Alcoholic liver disease: pathogenesis and new therapeutic targets. Gastroenterology. 2011 Nov;141(5):1572-85. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.09.002. Epub 2011 Sep 12. PMID: 21920463; PMCID: PMC3214974

[4] ^ Zhou J, Sun C, Yang L, Wang J, Jn-Simon N, Zhou C, Bryant A, Cao Q, Li C, Petersen B, Pi L. Liver regeneration and ethanol detoxification: A new link in YAP regulation of ALDH1A1 during alcohol-related hepatocyte damage. FASEB J. 2022 Apr;36(4):e22224. doi: 10.1096/fj.202101686R. PMID: 35218575; PMCID: PMC9126254.

[5] ^ Chen L, Zhang N, Huang Y, Zhang Q, Fang Y, Fu J, Yuan Y, Chen L, Chen X, Xu Z, Li Y, Izawa H, Xiang C. Multiple Dimensions of using Mesenchymal Stem Cells for Treating Liver Diseases: From Bench to Beside. Stem Cell Rev Rep. 2023 Oct;19(7):2192-2224. doi: 10.1007/s12015-023-10583-5. Epub 2023 Jul 27. PMID: 37498509.